This is not the ultimate guide for accessibility. You will not be an accessibility expert after reading this, not even a ninja! But I’d like to share what I have learned about accessibility in WordPress Themes. Hopefully that’ll help someone to build more accessible themes, and we can share ideas of how to make the web better place for all of us.

I’ve learned most of my knowledge from Joe Dolson and David A. Kennedy. They both contribute to the WordPress Accessibility Team and have been kindly answering my questions on Github and Twitter. Our goal is to understand the basics of accessibility and how we can prepare our themes to receive the official accessibility-ready tag.

What is accessibility and why should we care?

Web accessibility means that people can browse the web, with or without disabilities, using any device they might have. In this article, I mostly concentrate on people with disabilities including visual, auditory, physical, speech, cognitive, and neurological disabilities. We can improve our sites and help such people use, navigate, and interact with them.

Viljami Salminen talks about different input methods and performance in his article called The Many Faces of the Web.

On a bigger scale, I mean things like making our websites accessible to everyone. Making them work with different input methods like touch, mouse, keyboard or voice. Making them load and perform fast. Providing everyone access to this vast network of connected things. And if we don’t strive for all of this, what’s the point of working on the web?

If nothing else, you should care about the money! Brad Frost nails it in his article about accessibility and low-powered devices.

“Do you want to reach more customers?” the answer is always yes. When I ask them “Do you want your experience to load blazingly fast?” the answer is always yes. Both accessibility and performance are invisible aspects of an experience and should be considered even if they aren’t explicit goals of the project.

There it is. Make efforts to make Web experiences accessible and performant; make money.

Let’s start with the required parts of the puzzle.

.screen-reader-text for hiding text

Using .screen-reader-text is actually not required but I’ll use it in several examples. WordPress uses the CSS class .screen-reader-text to handle any HTML output that is targeted at screen readers. The purpose of screen-reader targeted text is to provide additional context for links, document structure, or form fields. This is helpful for whoever is using screen readers when browsing the web.

Since WordPress 4.2, the .screen-reader-text class is used in front-end code also, not just back-end. For example comments_popup_link() can output something like this by default:

4 Comments<span class="screen-reader-text"> on My article about accessibility</span>

Did you notice the .screen-reader-text class? The text on My article about accessibility is supposed to be hidden on screen but readable for screen readers. This provides additional information about what 4 Comments stands for and which article we’re talking about.

If you don’t have .screen-reader-text in your theme’s style.css that’s okay too. Then all users in this scenario would see the entire text (4 Comments on My article about accessibility), but nothing is broken. Naturally there is a plugin for adding support for .screen-reader-text as well.

Add .screen-reader-text in your theme’s style.css

The following snippet is the recommended method for adding a screen-reader class in your theme’s styles at the moment. You can also follow the Underscores theme for this and other recommended methods.

[gist id=”bee3e380c614542776de” file=”screen-reader-text.css”]

You can style the :focus styles differently but this a solid start.

Headings and headings hierarchy structure

Headings are important way to navigate your site. They are the first step most screen reader users take when they start to navigate your site. And regular users can also browse the a website more easily when there are structured headings.

But headings and heading hierarchy structure can be challenging, I certainly have had issues with headings in my personal experience. Should we use just one H1 element on each page? Can there be more than one H1? What about other headings: H2, H3 and so on?

With the acceptance of HTML5 standards, there can be more than one H1 on each page, but it’s important to be consistent with your headings hierarchy. Here is example of my blog page headings structure:

[gist id=”bee3e380c614542776de” file=”heading-structure-blog.html”]

And again for single posts:

[gist id=”bee3e380c614542776de” file=”heading-structure-post.html”]

The problem is that the headings hierarchy breaks if a user enters H1 in the article text or mixes headings in the wrong way. Plugins that output markup may also mess with the hierarchy.

Read more detail info about heading hierarchy structure and be consistent in your theme. And as a writer, think about the hierarchy structure of your theme and try not to break it. 🙂

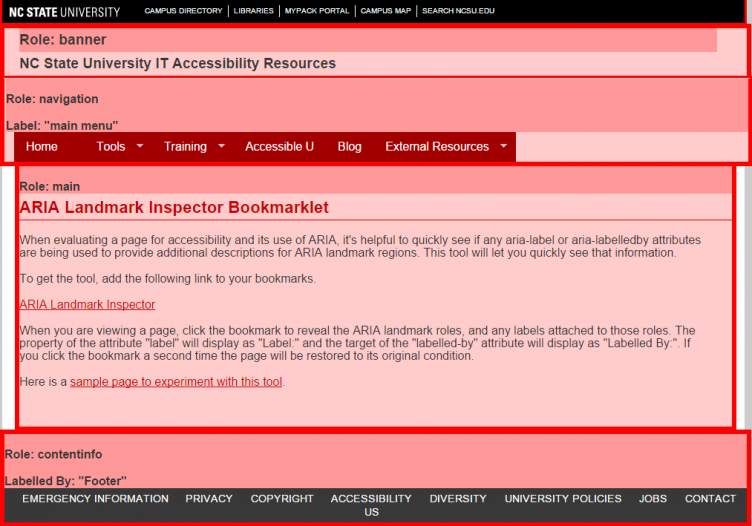

ARIA landmark roles

Aria landmark roles programmatically identify sections of a page. This helps navigate to various sections of a page for assistive technology users.

These are the most common roles:

- header:

role="banner" - main content:

role="main" - sidebars:

role="complementary" - footer:

role="contentinfo" - search form:

role="search" - navigation menus:

role="navigation"

If the same role appears more than once on a page, you should provide an ARIA label for that role:

[gist id=”bee3e380c614542776de” file=”aria-labels.php”]

Try not to use too many ARIA landmark roles. Otherwise it wouldn’t be helpful for screen reader users to navigate your site. Ten to fifteen roles is probably a good rule of thumb as a maximum limit.

Here is a simple example for how your HTML structure could look with ARIA roles:

[gist id=”bee3e380c614542776de” file=”aria-roles.html”]

An the screenshot from Aria landmark inspector website:

Link text

Imagine your blog archive using ten Read More… links. That’s not very helpful for screen reader users browsing trough your links. In general, avoid repetitive non-contextual text strings.

Using the_content() function

By default the_content() function outputs more… text when using <!–more–> in post content. Fortunately, you can change this output using the function’s first parameter: $more_link_text. It’s recommended to use the post title for additional context:

[gist id=”bee3e380c614542776de” file=”read-more-the-content.php”]

This will output Read more <span class="screen-reader-text">My Article Name</span>, not just the repetitive Read More. Note that we’re using class screen-reader-text again, which means that the post title can be hidden (if theme supports it), but screen readers will still read it.

Using the_excerpt() function

By default the_excerpt() function adds [...] to the end of the excerpt. We can replace with something similar to what we used in the_content example, using the excerpt_more filter.

[gist id=”bee3e380c614542776de” file=”read-more-excerpt.php”]

That’s more like it. You can change the HTML structure, but you get the general idea how we added post title after the default text.

Descriptive link text

Try to be descriptive when using link text, and bare urls should not be used as link anchor text.

Bad example:

[gist id=”bee3e380c614542776de” file=”bad-link-text.html”]

Good example:

[gist id=”bee3e380c614542776de” file=”good-link-text.html”]

Controls

Let links be links, buttons be buttons, divs be divs, spans be spans to ensure native keyboard accessibility and interaction with a screen reader. Article links are not buttons. Neither are divs and spans.

All controls must also have text to indicate the nature of the control, but it too can be hidden inside the .screen-reader-class.

For example, when toggling a menu, the control should be a button, not a link, div or span.

[gist id=”bee3e380c614542776de” file=”button.php”]

You can always style the button using CSS. Many theme developers add a font icon indicating the menu, like the commonly named “hamburger menu.” This is a bad way of adding the font icon:

[gist id=”bee3e380c614542776de” file=”bad-font-icon-control.php”]

Font icons alone don’t have any meaning for screen readers. In general the best icon is a text label.

Instead you could do this:

[gist id=”bee3e380c614542776de” file=”font-icon-css.php”]

Then add the icon font using a pseudo element, such as #nav-toggle::before.

You can also use the icon font and .screen-reader-text together.

[gist id=”bee3e380c614542776de” file=”font-icon-and-screen-reader-text.php”]

Sighted users will see only the hamburger icon, and screen reader users will now understand that this control is for the menu.

Keyboard navigation

On ThemeShaper, there is fantastic article about keyboard accessibility. In short, users must be able to navigate your site using only a keyboard. For example people who are blind or have motor disabilities use the keyboard almost exclusively.

I’d like to challenge you to put your mouse away for a while and test your own website. Can you navigate through links, dropdown menu and form controls using the tab and shift + tab keys? Enter can be used to activate links, buttons, or other interactive elements.

:focus is important

Note that only links, buttons and form fields can be focused on by default. That’s why I keep noting that we should let links be links and buttons be buttons. Don’t try to replace them with divs or spans. Users should see and elements should have visual effects to notate their state when they navigate your site using a keyboard. This is where :focus steps in.

This is a poor implementation:

[gist id=”bee3e380c614542776de” file=”lose-focus.css”]

That disables outline style for all links! This is much better:

[gist id=”bee3e380c614542776de” file=”focus-styles.css”]

Now users have a visual effect — a dotted line around the link — on links when focused. You can style the thin dotted to something else, but do not disable it. Remember that you can of course style buttons using CSS also, for example to change the background on :focus.

Make sure that colors are not your only method of conveying important information. That will help color blind people to see visual effects.

Dropdown menus and keyboard accessibility

Have you tried accessing your submenus in a dropdown menu using only keyboard? If you can’t successfully do so, let’s see what we can do about that, starting with the current guidelines for navigation menus.

- Fails: Dropdown navigation menus are hidden using

display:none;and brought into view on:hover - Passes: Dropdown navigation menus are hidden using

position: absolute;and brought into view on:hoverand:focus, and are navigable using thetabkey - Better: Dropdown navigation menus are hidden using position: absolute; and brought into view on

:hover,:focus, and are navigable using either thetabkey or by using the keyboard arrow keys.

Once again, the Underscores theme has a good example of dropdown menu markup which is navigable using the tab key. I’ll hope there will be support for arrow keys in near future. I personally use Responsive Nav as a starting point for accessible, responsive menus.

We need some Javascript magic for enabling keyboard support for dropdown menus. For reference, checkout this navigation.js file. This is the basic idea:

- Each time a menu link is focused or blurred, set or remove the

.focusclass on the menu link. This is done with thetoggleFocus()function. - Add class

.focusyour stylesheet, where you have:hoverstyles for the menu. - You can now navigate your menu and submenus using the

tabandShift + tabkey!

There are some other aspects we should consider for more accessible dropdown menus:

- Use ARIA markup like aria-haspopup=”true” in menu items that have submenus.

- What about touch devices? Have you tried accessing submenus using iPad when menu is in “Desktop” mode? I believe touch support is also coming to the Underscores theme.

There could be another in-depth article for creating accessible, responsive menus so I’ll move on.

Contrasts

Color contrast is something we might have to compromise on in our design. We need to provide enough contrast between text and background colors so that it can be read by people with moderately low vision. There are many beautiful themes out there that use for example light grey colors but might not pass the guideline for color contrast.

Theme authors MUST ensure that all background/foreground color contrasts for plain content text are within the level AA contrast ratio (4.5:1) specified in the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.0 for color luminosity.

I test color contrast using Joe Dolson’s tester tool. Accessibility doesn’t make your site ugly or boring, that’s always you. 🙂 But it does set some preconditions we need to follow. Aaron Jorbin also has a great talk on color theory and accessibility from WordCamp Chicago 2014.

Skip links

A website’s primary content is usually not at the top of the page. There can be dropdown menus, header sidebars, search forms or other information before the main content. For keyboard and screen reader users it’s annoying to navigate this extra content over and over again before arriving at the main content. That’s why themes must have skip links, which help to navigate directly to content. The skip link is usually added in the header.php file after the body or first div tag.

[gist id=”bee3e380c614542776de” file=”skip-link.php”]

Make sure the link is one of the first items on the page and visible when keyboard focus moves to the link. We already did that when we added .screen-reader-text class in our stylesheet.

Also move focus to the main content area of the page when skip link is activated. I believe there is still a bug in WebKit-based browsers that prevents focus being moved, but once again, the Underscores theme has you covered offering a good example.

Forms

WordPress default comment and search forms are accessible-ready, but be careful if you tweak them. I have made mistakes doing so in the past.

Hiding the search button using .search-submit { display: none; }. Do not use this CSS if you want the content to be read by a screen reader.

A better option is the filter get_search_form, and add our now familiar .screen-reader-text class to the search form’s submit button.

[gist id=”bee3e380c614542776de” file=”search-button-hidden.php”]

If you use a custom searchform.php in your theme, remember to keep appropriate field labels and do not use only a font icon as the submit button.

[gist id=”bee3e380c614542776de” file=”searchform.php”]

In short from the guidelines:

- Use form controls that have explicitly associated

<label>elements.- Create feedback mechanisms (such as via AJAX) that expose responses to screen readers. Look at techniques with ARIA for further information.

Also keep an eye on a collection of patterns for creating accessible-ready WordPress themes. Like an accessible comment form powered by JavaScript and ARIA.

Images and alternative text

As a user I’ve failed to add alternative (alt attribute) text to my content images, at least good ones. I promise to improve! You see, blind people of course can’t see your content images. Computers and screen readers can’t determine what the image presents. That’s why there is alt attribute and guidelines for images.

- If there are images in template markup, like features images, they must utilize the alt attribute. Or provide the end user to enter alt text.

- All decorative images should be added via CSS versus inline. Examples of decorative images are lines for style or background images.

- Note that sometimes an empty alt=”” is the best choice.

Media

Sliders and carousels must not auto start by default. The same goes for videos and audios. This is mostly plugin territory, but it’s good to mention, especially as the broader web is more and more often auto-playing this content.

Not allowed

There are couple of things that are not allowed.

- Any positive tabindex attribute. Negative or zero value tabindex is allowed in specific circumstances (assessed on a case-by-case basis).

- The inclusion of the accesskey attribute.

- Spawning new windows or tabs without warning the user.

Build accessibility-ready themes

We have gone through the required guidelines for getting the official accessibility-ready tag in our themes when we submit them to the WordPress theme repository. It wasn’t that bad was it!

I challenge you to build an accessibility-ready theme when you start your next project. Or look into your current site and start with small steps, like adding better support for keyboard users. I hope this article will help you do that. Let me know in the comments if there are mistakes in the article, you have questions, or you have ideas for part two.

It doesn’t matter are you building themes for customers, commercial themes for marketplaces or free themes for WordPress.org. We can all improve our skills and create more accessible websites.

About the author: Sami Keijonen is a teacher who likes to learn about the web, WordPress, and life. He runs Foxland Themes.

Great article, Sami! Thanks! One slight issue – I’d actually recommend using “ instead of using CSS generated content directly on the button. Screen readers can read generated content, but will ignore information marked as aria-hidden. Since the information in an icon font isn’t really very usable as a character, it’s best to be able to prevent those from being read by screen readers.

Thanks for comment Joe!

So screen readers read content from CSS generated :before and :after pseudo-elements? I definitely did not know that.

It would be awesome if you could give small snippet how we should use Menu toggle button with font icon, text and aria-hidden combo.

Here’s an example:

https://gist.github.com/joedolson/113e0dff30a77d8b9f3c

In this example, I’ve chosen to hide the text using the .screen-reader-text class; but that’s mostly for demonstration. I’d actually encourage people *not* to hide that text – it’s useful for all users, not just users of screen readers. The important part is that the container for the dashicon is concealed from screen readers, so they don’t potentially read the empty content.

What will be read in an icon font is very unpredictable; but yes, they can read it. Here’s a great article about it: https://css-tricks.com/html-for-icon-font-usage/

Accompanying the menu toggle above, the JS that opens the menu should also change the value of the aria-expanded attribute to true and update the text of the button to ‘Close Menu’.

Found it in the spam.

Thanks for the gist example. And I agree, it’s useful for all users to show Open menu / Close Menu text. In that case we probably don’t even need the menu icon. But that’s another story.

Hey, Sami – I did write up a reply; but it seems to have gone missing. I’m assuming it’s been marked for moderation, since it contained a couple links – hopefully this message will bring that to attention.

Thanks a lot for this excellent article, comes just at the right time for me 🙂

You’re welcome 🙂

Love that you tied in the business case for accessibility. It’s a much easier sell to say “we can make more money this way” than “do this just because it’s the right thing to do.”

That’s true. And money can be good motivator to build better, more accessible sites.

Thank you so much for this amazing article!

Do we have a list of screen reader devices and how they render the website? What’s is the important things that we should know about the ability of parsing and reading CSS/HTML of screen readers?

JAWS is popular and here are list for other screen readers:

http://webaim.org/projects/screenreadersurvey5/#primary

We probably need another article to answer your other questions, but here is a good start:

http://webaim.org/techniques/screenreader/#how

Fantastic article, Sami! So detailed! Thanks for sharing what you’ve learned with the community and for spreading the word about accessibility.

Thank you and Joe for answering my accessibility questions and helping me out for writing this in the same time.

Great article Sami,

Very useful, thank you for sharing this.

I do think most of us have got a good grip on ‘mobile-friendly’ design now, but the time is right for us all to really embrace ‘human-friendly’ web development. From both a human and business point of view, inclusive is a win-win.

Thanks for feedback. Let’s build web for humans, not just for devices.

Thank you for this comprehensive article!

We are working to improve accessibility in our Federal University’s website and one of the recommendations of our Government’s web standards is the use of “accesskey” attributes for skip links. Could someone please elaborate on why is this practice not allowed by the WP accessibility team?

Thanks for commenting!

Webaim has good article about problems using accesskey.

Thanks again!!

Great post. Forging new habits is never easy – but I realize how important it is for me to incorporate accessibility into my design and development process.

My question: What is the purpose of the title tag for images in the WordPress Media manager? I understand why alt text is important – not sure what the value of the title tag is?

Title tag was removed from Insert/edit link modal box in WP 4.2. But I don’t know why it’s kept in Media manager. Here is good conversation about title attribute, read the comments also.

Very informative post, it would be great if we have many more great looking themes that are accessible, I often find that people tend to think accessibility mean poor design/user experience. And yes your social sharing icons are not accessible with screen reader. Jetpack sharing buttons are accessible.

Great looking themes can be accessible, there is no doubt about that.

If you’re referring to this site, Brian will make some improvements 🙂

Note that I’ll be updating the examples if there is some new info. For example I have always wondered why there is :hover and :active in .screen-reader-text class. Well, just let them go.

Thanks for the write up on such an important topic. I worked at an agency that specialized in the senior living (retirement) market and realized very early on just how important it is to build sites that are accessible. Every day more and more people who are seniors are hopping on the internet, many of them who have degenerative conditions where a bad design can truly affect how well they can use a site.

Some of the biggest issues we would see were low contrast, poor choice of colors ( pale yellows and blues), confusing site architecture which was difficult for users with memory difficulties, and sometimes even kludgy mobile interfaces that were hard to use if someone had arthritis.

The way we design websites can directly affect the physical well being of someone physically and mentally, especially if the site is important because it relates to their health such as a doctors website, or mobile device that they rely on for communications (screen reader).

Thanks Luke for pointing out important issues like low contrast and poor choice of colors.